Francisco Costa’s call sign is M0HOJ—although he is not a US airman but a UK-based balloon hunter and senior field engineer at CRFS. Balloon hunting might be a fringe sport, but Francisco has been hunting and tracking them enthusiastically for many years. He started when commercial equipment became available to track weather balloons, meaning anyone could participate.

99 weather balloons

In the UK, the Met Office launches more than 4300 weather balloons a year to obtain atmospheric data that inform the Public Weather Service’s weather updates and provide civil and military aviation with critical information.

Flying unnoticed 68,000 feet above the ground, weather balloons are often equipped with radiosondes—small instruments that transmit data at around 400 MHz to ground stations as the balloon ascends through the atmosphere. The receivers started transmitting their position when the balloons were fitted with GPS.

While the Met Office is concerned with the ascent and flight of the balloons, after they have fulfilled their intended purpose, the agency cares little for their descent and afterlife. However, for the hunters, one man’s non-biodegradable plastic weather balloon is another man’s prize to sell on eBay.

Weather balloon hunters track the descent of individual balloons and, using online resources and available weather data, estimate the rough area it will land. When it’s close to the ground, balloon hunters like Francisco jump in their cars and, tracking the balloon’s GPS, dash off to beat rival hunters and claim their prize.

Until recently, hunters had to own their own receiver, antenna, and software tracking. But the internet has democratized balloon hunting thanks to several master hunters who gather key information and publish it on websites for everyone to use freely. Francisco likes sondehub.org.

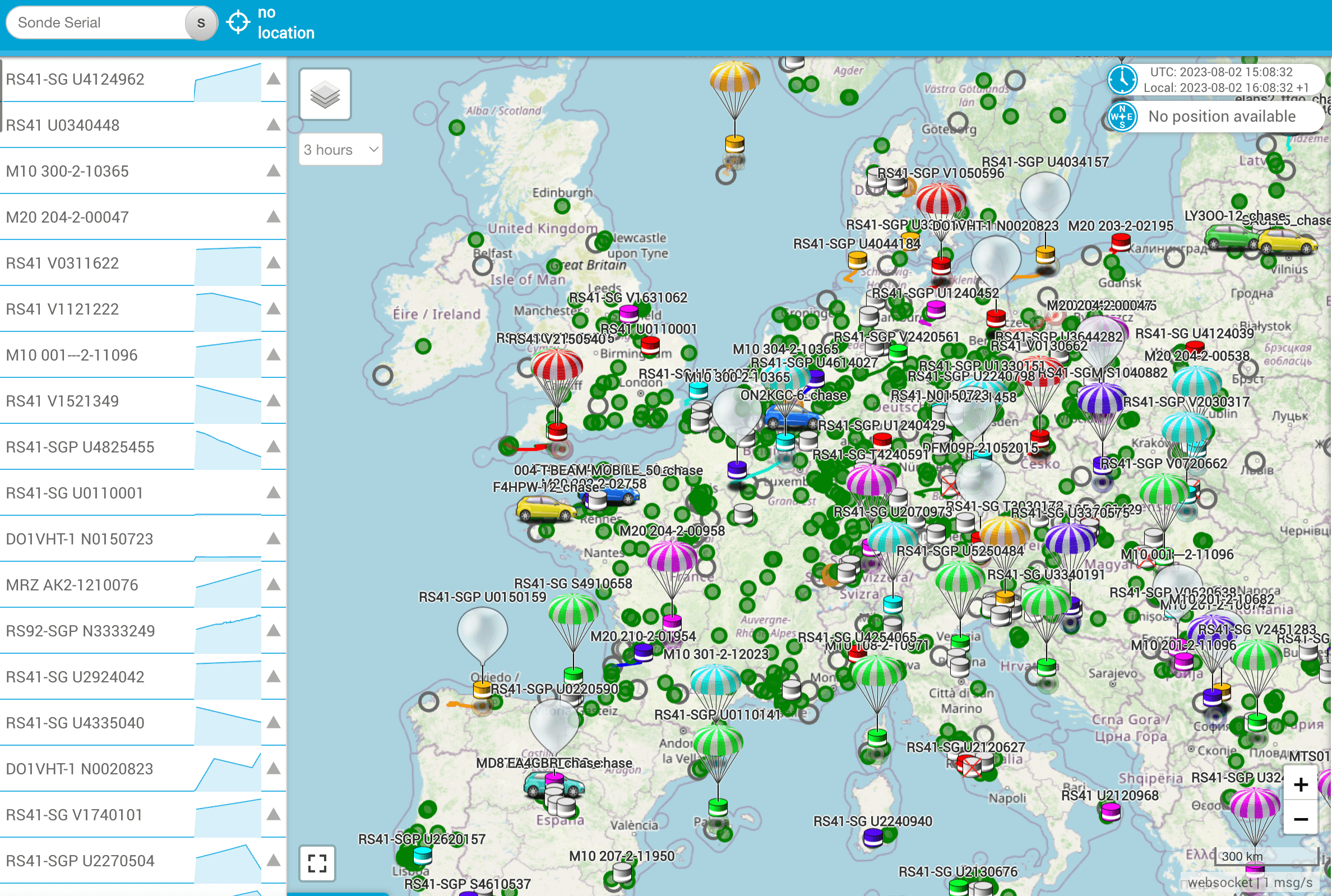

Figure 1: Map of Europe (from sondehub.org) showing ground stations (green), launch sites (grey), ascending balloons (white), and descending balloons (parachutes)

Mapping the hunt

The green circles in the sondehub.org map above represent ground stations equipped with instruments such as ground plane antennas and SDR receivers. These are manned mainly by amateur radio enthusiasts who track weather balloons and report their position on the internet. The empty grey circles show the balloon launch sites. Hunters can click on the circle to see the launch schedule and the exact frequency on which the sonde is transmitting. (Stations tend to coordinate launching balloons to compare the data.)

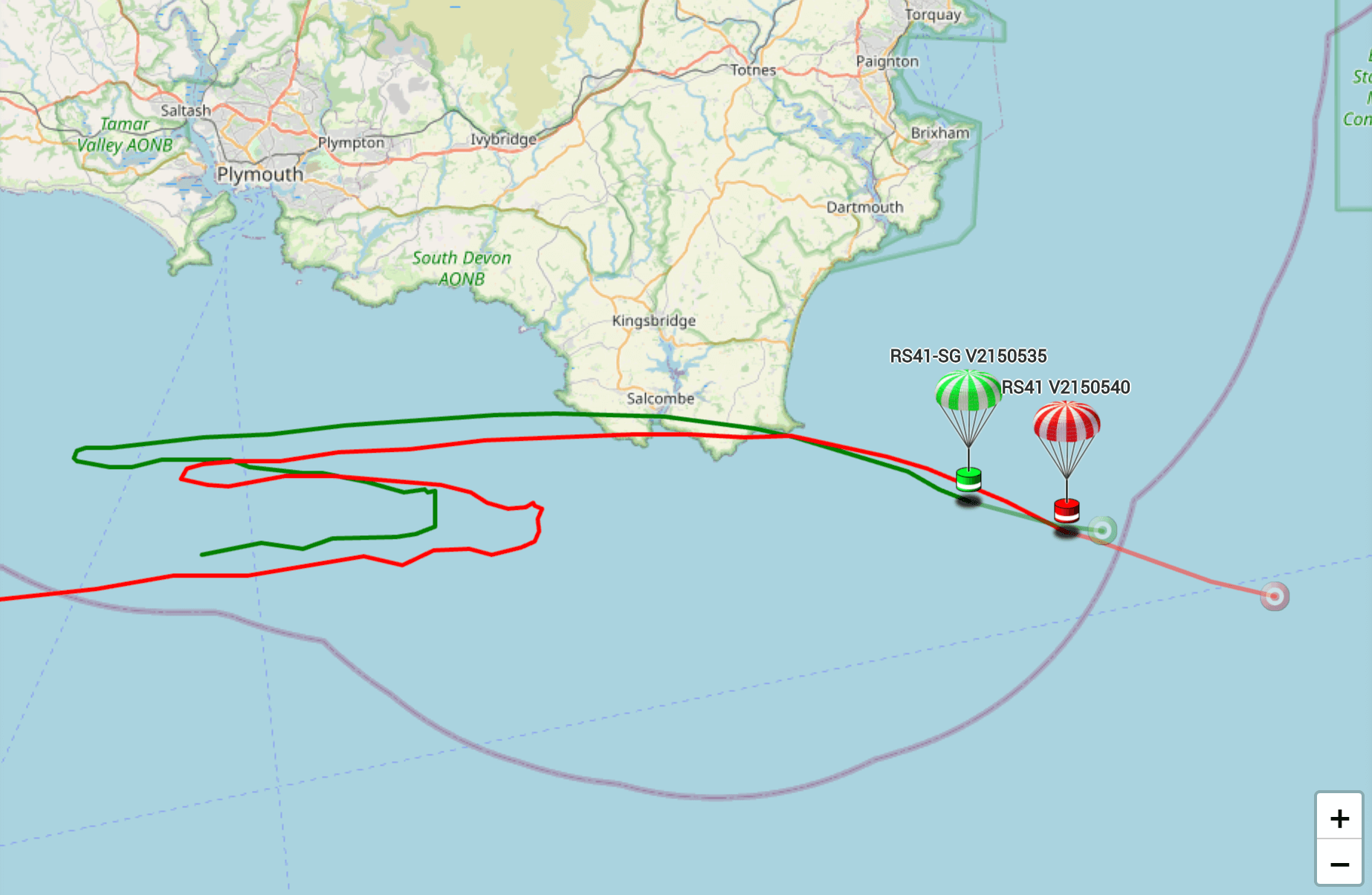

White balloons are in ascent, whereas parachutes depict descending balloons. The software also shows the balloons’ flight paths and predicts where descending balloons will land, as seen in the image below. Note: however fanatical some balloon hunters are, there have been no known cases of ‘fishing’ weather balloons in boats rather than cars.

Figure 2: Flight path of descending balloon and predicted landing site (from sondehub.org)

The endgame

Francisco monitors radiosondes predicted to land close to his home. When a balloon is roughly a few miles away, he uses Google Maps to navigate to the expected landing site—first by car and then on foot.

At this point, reviewing the last altitude the balloon transmitted to the closest station can provide a clue as to where it may land, as the predicted landing site is not always correct. Balloons can land up to half a mile away from the expected location. Francisco’s portable scanner comes in handy as he tries—by trial and error—to find a strong signal for the balloon. But he must be quick. He’s not only competing with other hunters for the prize. “One guy from Milton Keynes gets everything,” says Francisco. He’s also racing against the clock as sondes only transmit for eight hours after launch to prevent interference with the next balloon, which will transmit on the same frequency.

Hunters, therefore, have only a brief window to detect a signal and locate the balloon—after this, finding it is pure luck.

On his last hunt, Francisco teamed up with the private land owner to search for the fallen balloon—finally finding it in a farm field. As the radiosonde operates on a licensed frequency, he first turned it off to prevent interference. He then checked the radiosonde number on the label and reported (on sondehub.org) that M0HOJ had found the device in a field.

Bringing hobbies to work

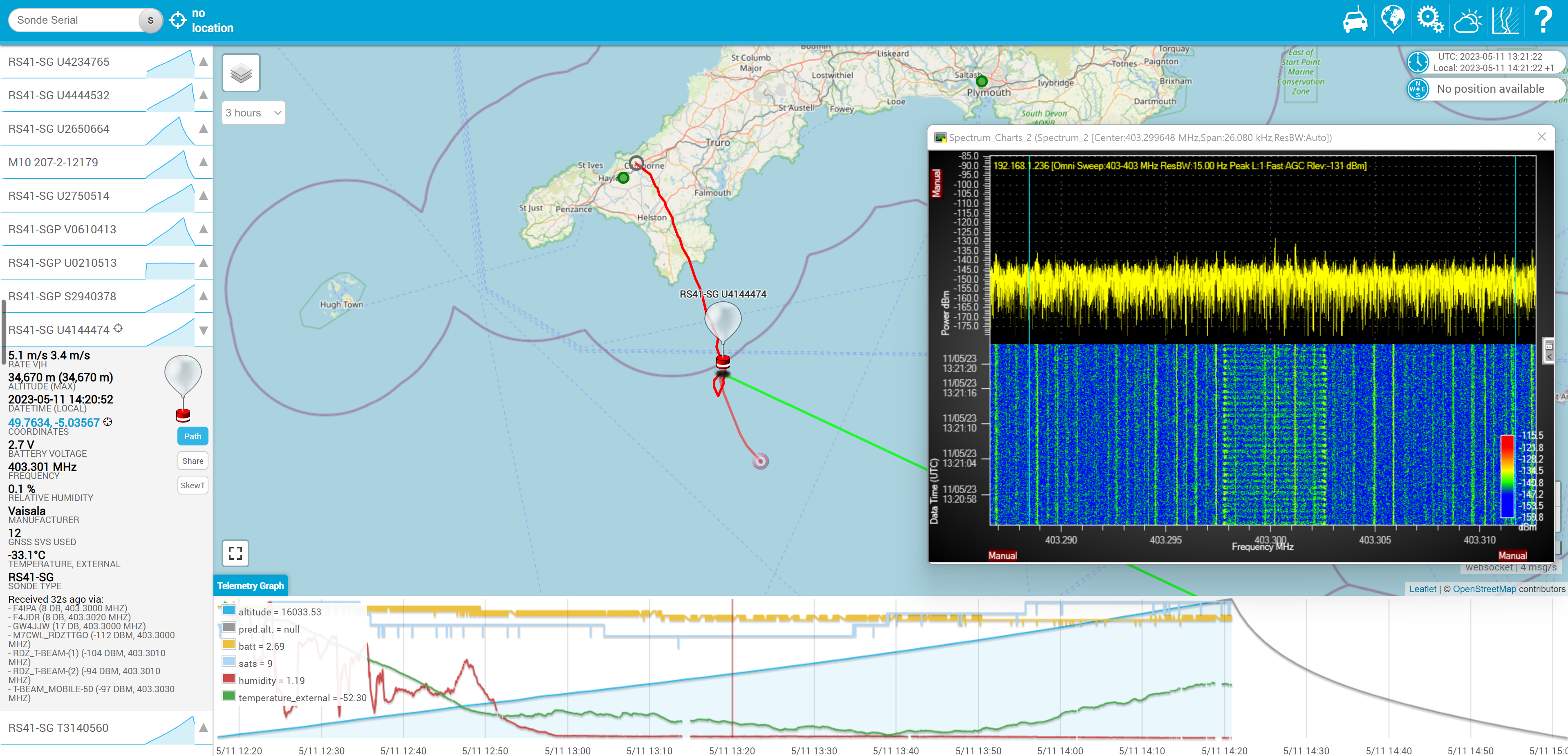

Francisco was curious about the difference between the advanced technical equipment at work and his amateur devices. So, he used an RFeye Node installed on the roof of his Cambridge office to pick up a radiosonde launched from the Nottingham Weather Centre, around 90 miles away, transmitting at 405.5 MHz. Each UK station uses a unique frequency, so it is possible to know exactly which balloon you are tracking.

He noticed a radiosonde transmitting at 403.301 MHz—the frequency used by the station in Camborne, Cornwall, over 300 miles away and well out of range. The equipment is only supposed to be capable of detecting transmissions up to 217 miles away. But over half that distance again? “Impossible,” said Francisco. “Unless you have specialist equipment such as a receiver for the target frequency, a tuned filter, and a preamplifier.”

Figure 3: Position of the balloon being tracked and the spectrum showing the noise floor and waterfall

Yet there he was, tracking a weather balloon off the coast of Cornwall from north Cambridgeshire. And he was doing it with passive equipment—a general antenna with no filtering connected straight to the Node. This was remarkable and only possible thanks to the sensitivity of CRFS’ RF receiver (Nodes), noise floor, which was around -155 dB.

Francisco knew that noise floor level is rarely encountered in real-world scenarios; it is more commonly seen in highly specialized laboratory settings.

At first, I said I didn’t believe him. “So, I’ll show you,” said Francisco.

%20CTA%20cover.png)

Brochures, Guides & Survey's

RFeye Node Overview

Discover our advanced superheterodyne RF technology for superior sensitivity, frequency stability, and selectivity. Compare Node specifications, view the new RFeye Node models, and discover what makes them unique.

Jaimie Brzezinski

Jaimie Brzezinski is Head of Content for CRFS. His specialty is turning highly technical ideas into engaging narratives. He has 15+ years of experience in writing technical content and building global teams of subject matter experts.